Category:Impact Story10 min read

Category:Impact Story10 min read

Across Minnesota, support for artists and culture bearers goes far beyond the financial, stretching into less traditional but equally important forms of sustenance.

In addition to the customary financial and physical support creatives need to do their work, organizations across the state have broadened their efforts by working to connect artists and culture bearers to each other and their broader communities, as well as validate and advocate for their work.

This shift is not only helping support a new generation of artists and culture bearers, but also strengthening the arts infrastructure in communities across the state, elevating the perspectives of creatives who are often overlooked by mainstream institutions, and making a big difference for artists of color and folk artists in particular.

Organizations at the forefront of these shifts include Minneapolis’ Public Functionary, a nonprofit program that cultivates and supports emerging artists, particularly those from Black, Indigenous, and Immigrant communities, and the New York Mills Regional Cultural Center, which does the same for folk artists in northern Minnesota.

When Tricia Heuring, Public Functionary’s artistic director, first met artist Leslie Barlow in her studio, Barlow was struggling with self-doubt. “Because she was painting [with a] mixed race identity and thinking about race in different ways, she wasn’t really finding support in the arts community for her work,” Heuring recalls. Barlow remembers the warmth of Heuring’s support. “I could see that she connected with my work, [she] was very affirming.”

Video produced by Line Break Media

The relationship an artist has with their practice isn’t always easy—sometimes creativity and the ideas that fuel it are constrained by the self-doubt that can accompany an exploration of uncharted creative frontiers. Finding a way to make a living from creative pursuits isn’t easy. Neither is the practice of creating culture work like folk art, which can be marginalized or just not taken seriously by conventional arts institutions and venues, as can be the case with the work of people of color more broadly.

Today Barlow is Public Functionary’s studios director, which operates out of the Northrup King Building in Minneapolis’ Northeast Arts District. What started as a standalone space of around 2,000 square feet now occupies just over 20,000 square feet in a massive arts building that’s long lacked diversity.

“Initially, we wanted the studios to be a resource for emerging artists of color and other artists that have experienced marginalization,” Barlow says. But over time the needs of Public Functionary’s artists have changed, and the organization always follows suit. “Since those early days, the artists have named all these other ways that they could be supported.”

Now Public Functionary does everything from hosting critiques and workshops to bringing in curators and other artists to talk about their work and offering mentorship opportunities. “The whole thing together forms a community space where artists are able to see themselves in relation to each other and a growing arts ecosystem,” Heuring says.

Minnesota’s art world is transforming beyond the Twin Cities as well. Tucked into a small town in Otter Tail County, the New York Mills Regional Cultural Center started as a residency program back in the ‘90s. Today, it’s a vibrant community center that offers gallery space for shows and performances as well as workshops and classes alongside a gift shop filled with artist-made items and locally made goods like maple syrup and Scandinavian treats that stem from the town’s Finnish roots. For the last 32 years, the center has hosted its annual Great American Think Off, a philosophy competition where invitees submit essays that inspire a live debate focused on civil discourse each June.

“We’re kind of everything to everyone, partly because of our location in a really rural area,” explains Betsy Roder, the center’s executive director. She says that when the center opened, New York Mills’ population was around 1,000 people. Today it’s just over 1,300.

“Part of that growth can really be attributed to the cultural center—within the first five years of our opening, there was a 40% job growth in the community, and 17 new businesses opened or moved to town. Art is important for art’s sake, and it also drives economic development and community development not just in New York Mills, but regionally,” Roder says.

A lot of the center’s efforts stem from highlighting and celebrating the specialness of rural places and the unique art, culture, and creativity they produce. “We’re just embracing that rural culture and heritage. Part of our vision statement is to both celebrate the local and provide a window to the world,” she says. For Roder, there’s no reason to view rural and urban areas as opposed to or better than the other.

But New York Mills doesn’t stop with arts. They see themselves as a true and full community partner in all of the multifaceted ways it entails. When the pandemic was raging and George Floyd was murdered in 2020, the center did what it could to contribute to public health and anti-racism efforts. “We were constantly posting about masking and distancing. We did a whole learning series about anti-racism” Roder says. “We really try to embrace the needs that our community and our region have.”

It’s the far-reaching difference that organizations like the New York Mills Regional Cultural Center and Public Functionary make, in and across their communities and beyond, that drives the funding strategy behind McKnight’s Arts and Culture Program.

“We’re really interested in supporting organizations that invest in artists and culture bearers, and that starts with ensuring they have what they need to make a good living,” says Caroline Taiwo, an Arts & Culture Program Officer at McKnight. “Organizations like Public Functionary and the New York Mills Cultural Center demonstrate the value of creating a space where arts and culture bearers can come together, learn from each other, and have the resources and development they need to grow in their careers and shape the field and their futures.”

Another facet of the program is the elevation of culture bearers, whose work is often anchored in Indigenous and other traditional practices—the “people who are doing more folk art, storytelling work, community building through art and creative practice, and elder work,” Taiwo adds. It’s also about partnering with and funding organizations that have been underfunded or even entirely left out of the current funding system, and thoughtfully spreading resources around the state.

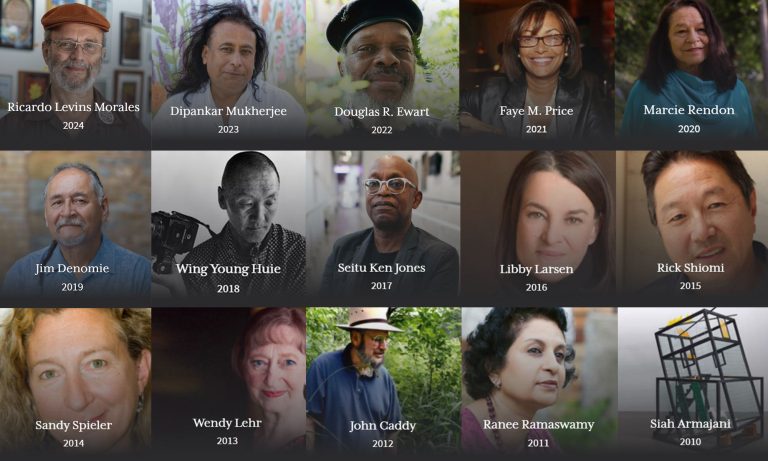

The program doesn’t just support arts organizations, though. Its Artist and Culture Bearers Fellowship program supports artists directly. Since its inception in 1982, the program has invested more than $38 million in the program that has funded 2,056 fellows across disciplines— from playwriting, choreography, and theater arts to music, textile arts, and ceramics—to date.

The fellowship program is an initiative inside the larger Arts and Culture program. It works with partner institutions across the state to award and disseminate the $25,000 of unrestricted funding the fellows receive. Partner institutions also help to connect fellows more deeply to others in their creative communities.

From the fellowship program to grants made to leading organizations like Public Functionary and the New York Mills Regional Cultural Center, McKnight’s goal is furthering a broad interpretation of what effective support for creatives entails because it benefits everyone regardless of their relationship with the arts.

“We know there are artists everywhere,” Taiwo says. “Ensuring more artists and culture bearers can thrive here strengthens the economy, our health, social connections, and quality of life in more communities across our state.”