Broadening what counts as knowledge and expanding participatory research methods is key to growing more equitable food systems. That’s the lead finding of a recent report in Nature Food, “Knowledge democratization approaches for food systems transformation,” co-authored by Jane Maland Cady and Paul Roge, among many others.

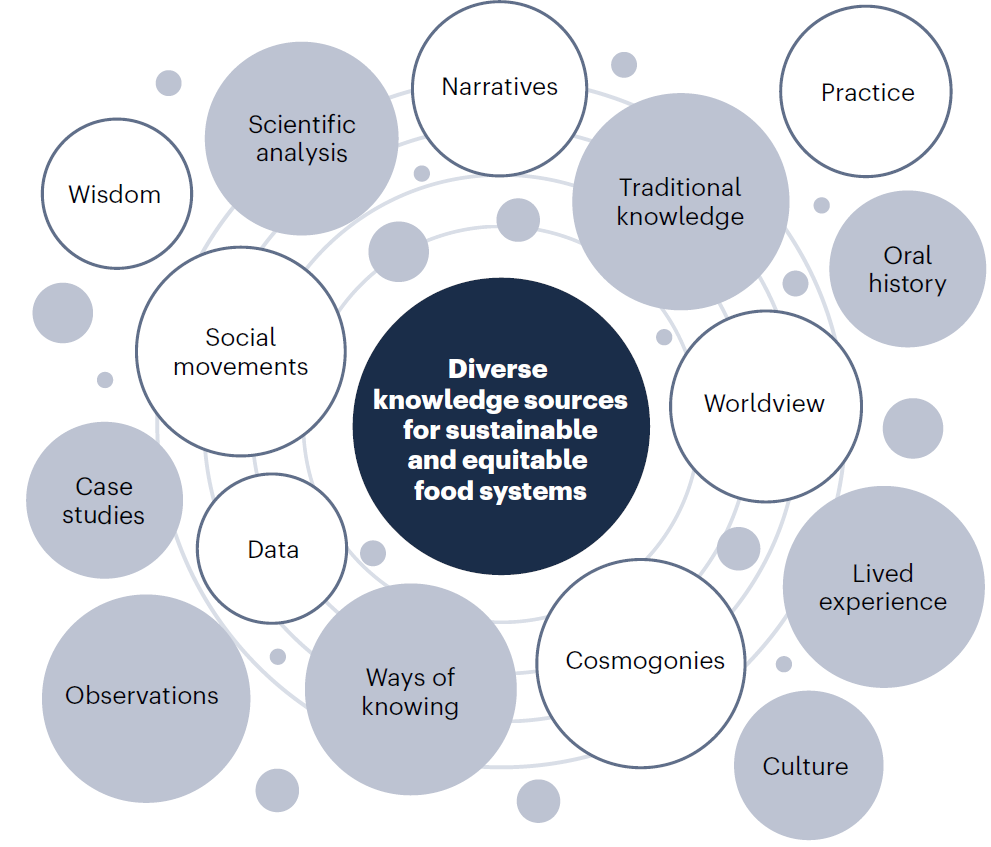

Traditional, Indigenous, and place-based knowledge offer essential insights for sustainable pathways, yet they are regularly excluded from decision-making about agricultural and food system funding, policies, and actions. Centering a diversity of knowledge and ways of knowing is critical to deepening democracy in agricultural research, innovation, and implementation to address these issues and improve outcomes, the authors conclude.

The principles outlined in the article emphasize the importance of epistemic justice, intercultural co-creation, and knowledge mutualism and exchange in democratizing knowledge-policy processes. These principles, the authors argue, are essential for addressing biases and empowering marginalized communities in shaping food system transformations.

Led by Samara Brock from Yale University, the article is an outcome of an international process convened by the Global Alliance for the Future of Food on the Politics of Knowledge that brought together food systems leaders to strategize on advancing research and evidence for agroecology. Drawing from case studies worldwide, the authors highlight innovative approaches that involve local actors in knowledge production and exchange.

Featured as a key model in the report are farmer research networks supported by McKnight’s Global Collaboration for Resilient Food Systems, which combine scientific knowledge with Indigenous traditional and local knowledge in communities of practice that span ten countries in the high Andes and Africa. These networks bring together farmers, research institutions, development organizations and others to improve agriculture and food systems for all. In a co-created process of sharing and building knowledge, these networks seek ecological solutions tailored to specific regions, considering local farmers’ needs, priorities, and wisdom—including those of women and other historically marginalized groups. Since 2013, the Foundation has supported 30 farmer research networks ranging in size from 15 to more than 2,000 farmers.

“We believe in both results that can be measured and results that can be seen and observed in ways that may not be taught at universities,” shared Jane Maland Cady, program director for McKnight Foundation’s Global Collaboration for Resilient Food Systems. “In our decades of practice, we have found that when local farmers have a say in the health of their food, water and resources, and share their knowledge, they are a force for global change.”

“When research is developed and conducted by farmers, it becomes more relevant to rural communities’ concerns, needs, and interests,” says Paul Roge, senior program officer with McKnight’s Global Collaboration for Resilient Food Systems. “With greater engagement and ownership of the research, farmers are more likely to share and engage with others in ‘farmer-friendly’ ways, such as through farmer-to-farmer demonstrations and dissemination of educational resources on techniques for solving agricultural problems of relevance to smallholders. Power dynamics are negotiated among farmers and scientists in a more horizontal way, so that both can design and co-create research and knowledge dissemination practices.”

The authors make three recommendations intended for those who fund, design, and carry out food systems research:

- Support research that focuses on system-wide change, rather than on narrowly defined quantitative criteria such as, for example, agricultural yields. This will entail looking beyond what is easily quantifiable to incorporate broader social, cultural and ecological drivers and consequences.

- Build capacity and support for transdisciplinary, participatory, farmer-led and Indigenous-led research, funding training as well as the maintenance of locally governed repositories of knowledge.

- Support knowledge and evidence mobilization and communication, such as peer-to-peer research and networking, multi-actor advocacy coalitions and the participation of farmers, Indigenous peoples and their organizations in research, policy and decision-making.

As we collectively strive for food systems that are capable of nourishing populations and regenerating ecosystems, incorporating a diversity of knowledges into decision-making can advance innovative and time-tested solutions to food systems transformation.