Fünf Jahre nach dem Mord an George Floyd sind Künstler und Kulturschaffende in Minnesota weiterhin unverzichtbar, um von einer gerechteren, kreativeren und erfüllteren Zukunft zu träumen und diese aufzubauen. Wandmalereien, Schablonenmalereien, Lieder und andere aus der Tragödie des Jahres 2020 entstandene Kunstwerke halfen Gemeinden in den Twin Cities und im ganzen Land, die Komplexität zu bewältigen, Gerechtigkeit zu fordern und den Heilungsprozess zu beginnen.

In Minnesota und anderswo reagieren Künstler nicht nur auf den Moment, sie gestalten ihn mit. Von Großstädten bis zu Kleinstädten, von Galeriewänden bis zu Küchentischen – sie stellen sich gegen Ungerechtigkeit, heilen die Wunden der Gemeinschaft, bauen Verbindungen auf und geben Führung.—DEANNA CUMMINGS, ARTS & CULTURE PROGRAM DIRECTOR

Minnesota ist die Heimat von über 30.000 Künstlern und mehr als 1.600 Kunstorganisationen. Von ländlichen Gemeinden bis hin zu Großstädten tragen Künstler und Kulturschaffende dazu bei, Hauptstraßen zu revitalisieren, Raum für Heilung zu schaffen und neue Türen in unseren Herzen und Gedanken zu öffnen, die zu einem besseren Verständnis zwischen uns führen. Am fünften Jahrestag von George Floyds Tod befindet sich unsere Nation in einer weiteren Phase der Unsicherheit. Um uns dabei zu helfen, den gegenwärtigen Moment zu verstehen, haben wir sechs bedeutende Künstler und Kulturschaffende gebeten, über zwei Fragen nachzudenken:

- Wie können Kunst/Künstler/Kulturträger zum sozialen Wandel und zur Heilung der Gemeinschaft beitragen?

- Was inspiriert oder motiviert Sie in diesen herausfordernden Zeiten?

Hier ist, was sie uns erzählt haben.

Marcie Rendon

Autor, Dramatiker, Dichter, Aktivist für Gemeinschaftskunst

Kunst heilt. Sie hat die Kraft zu heilen, zu nähren und zu inspirieren. Indem wir unsere Geschichten schreiben, unsere Lieder singen und unsere Visionen malen, halten wir die Hoffnung am Leben – unsere eigene und die anderer. Wer Schönheit schafft, kann nicht zerstören. Wir brauchen in dieser Zeit mehr Schöpfer. Mehr Visionäre. Mehr Menschen, die Schönheit und Hoffnung teilen.

Wie können Kunst/Künstler/Kulturträger zum sozialen Wandel und zur Heilung der Gemeinschaft beitragen?

Kunst heilt. Kunst hat die Fähigkeit zu heilen, zu nähren und zu inspirieren. Indem wir unsere Geschichten schreiben, unsere Lieder singen und unsere Visionen malen, halten wir die Hoffnung am Leben – unsere eigene und die anderer. Wer Schönheit schafft, kann nicht zerstören. Wir brauchen in dieser Zeit mehr Schöpfer. Mehr Visionäre. Mehr Menschen, die Schönheit und Hoffnung teilen. Und ich spreche nicht nur von schönen Bildern oder leuchtenden Worten des Friedens und der Liebe. So schön das auch sein mag, wir brauchen mehr Menschen, die Mitgefühl, Großzügigkeit und gegenseitige Abhängigkeit inspirieren. Sozialer Wandel und gesellschaftliche Heilung erfordern visionäre Künstler und Kulturträger, die Die Wahrheit sagen. Die mit Liebe führen. Besonders Kulturträger wissen, dass genug für alle da ist. Wir leben nicht in einer Welt des „Mangels“. Wir leben in einer Welt, die die Angst vor Ressourcenknappheit schürt. Unsere Ältesten versichern uns, dass die Erde uns allen alles gibt, was wir brauchen, wenn wir sie schonend behandeln. Insbesondere Künstler dokumentieren die Realität. Sie scheuen sich nicht vor der Wahrheit, sondern finden Wege, anderen die Wahrheit so zu vermitteln, dass andere sie sehen, fühlen, schätzen und sich davon inspirieren lassen können. Kunst heilt. Heiler schaffen Kunst.

Die Wahrheit sagen. Die mit Liebe führen. Besonders Kulturträger wissen, dass genug für alle da ist. Wir leben nicht in einer Welt des „Mangels“. Wir leben in einer Welt, die die Angst vor Ressourcenknappheit schürt. Unsere Ältesten versichern uns, dass die Erde uns allen alles gibt, was wir brauchen, wenn wir sie schonend behandeln. Insbesondere Künstler dokumentieren die Realität. Sie scheuen sich nicht vor der Wahrheit, sondern finden Wege, anderen die Wahrheit so zu vermitteln, dass andere sie sehen, fühlen, schätzen und sich davon inspirieren lassen können. Kunst heilt. Heiler schaffen Kunst.

Was inspiriert oder motiviert Sie in diesen herausfordernden Zeiten?

In dieser Zeit inspirieren mich der Mut und die Tapferkeit anderer Menschen. Ich finde Hoffnung in Humor und Großzügigkeit. Meine Kinder, Enkel und Urenkel, die überleben, kämpfen, durchhalten und lachen, trotz der Völkermordpolitik, die seit Generationen herrscht und besagt, dass niemand von uns hier sein sollte. Sie geben mir jeden Tag Hoffnung. Andere Menschen, die mich besonders inspirieren, sind Menschen wie Bao Phi, deren Gedichte Wahrheit und Liebe zu Familie, Gemeinschaft und gerechter Wut über Ungerechtigkeit zum Ausdruck bringen. Sharon Day, Ojibwe Mide-Wasserläuferin, inspiriert mich ebenfalls mit ihrem Einsatz nicht nur für das Wohl der indigenen Gemeinschaft, sondern für alle Menschen, die Wasser zum Überleben brauchen. Ihr stiller, demütiger Einsatz, Dinge gezielt in Ordnung zu bringen, ist ein Vorbild für alle, die es beobachten möchten: Aufstehen und einen Schritt vor den anderen setzen kann die Welt in Ordnung bringen, wenn es mit guter Absicht geschieht. Mein Freund Mark, Ojibwe-Trommelhalter, der erblindete, aber weiterhin Ojibwe-Lieder mit und für zukünftige Generationen singt. Meine Künstlerfreunde, die wissen, wie man angesichts all der Unterdrückung mutig und lautstark auftritt. Es gibt so viel Schönheit auf der Welt, so viel, wenn wir uns nur darum kümmern und es wagen, danach zu suchen.

Vor Jahren schrieb ich: „Ich lache jedes Mal über ihre Versuche, uns umzubringen, wenn ich einen wilden Rosenbusch aus dem Beton entlang der I94 wachsen sehe.“

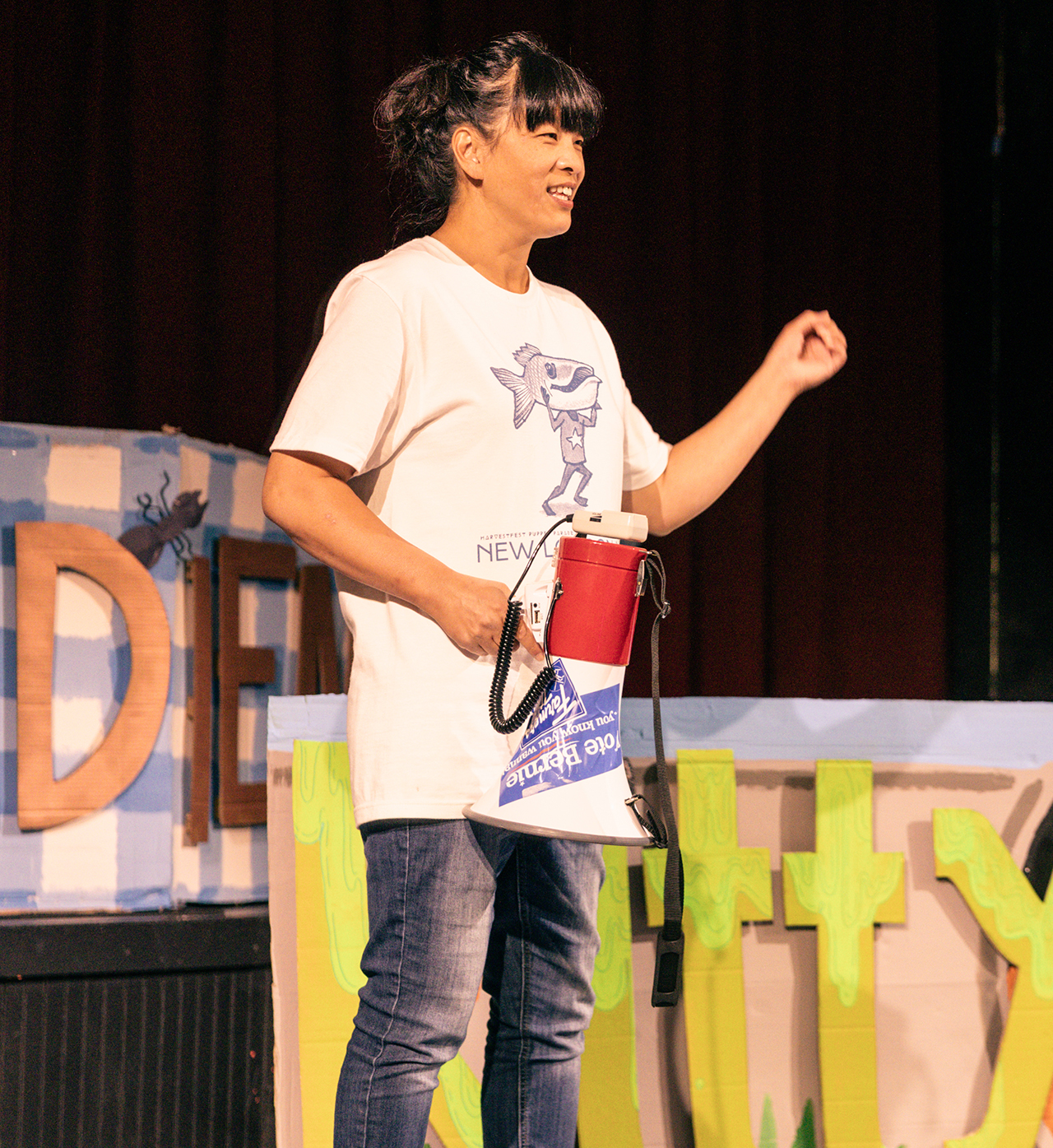

Bethany Lacktorin

Performancekünstler, Veranstalter, Medienproduzent, Musiker

Der Austausch von Geschichten und künstlerischen Erlebnissen schafft einen sicheren Rahmen, um einander kennenzulernen und gemeinsam Entdeckungen zu machen. So können menschliche Verbindungen lange genug gedeihen, damit Heilung beginnen kann. Selbst wenn es nur eine Person ist, sind die Auswirkungen in einer Kleinstadt tiefgreifend, wenn nicht gar weitreichend.

Wie können Kunst/Künstler/Kulturträger zum sozialen Wandel und zur Heilung der Gemeinschaft beitragen?

Als Person of Color im ländlichen Minnesota zu leben, kann eine besondere Bürde mit sich bringen. Vielleicht ist es eine leichte Rolle als Brückenbauer. Oder vielleicht ist es manchmal eine gewichtigere Rolle als Anstifter sozialen Wandels. Trotz dieser Rollen ist Tokenisierung immer noch real. Ob es nun die Tokenisierung des Künstlers oder der dargestellten Identität ist, ich habe sie als eine Art höflichen Ausdruck von Neugier akzeptiert. In diesem Umfeld sind künstlerische Prozesse unbeabsichtigt zu einer Möglichkeit geworden, Neugier zu rahmen und einzudämmen. Das Teilen unserer Geschichten und Kunsterlebnisse bietet einen sicheren Rahmen, um voneinander zu lernen und gemeinsam Entdeckungen zu machen. Hier können menschliche Verbindungen lange genug gedeihen, damit Heilung beginnen kann. Selbst wenn es nur eine Person nach der anderen ist, sind die Auswirkungen in einer Kleinstadt tiefgreifend, wenn nicht sogar weitreichend.

Was inspiriert oder motiviert Sie in diesen herausfordernden Zeiten?

Kunst gilt seit langem als Instrument, sozialen Wandel anzustoßen. Sozialer Wandel beginnt mit Verbundenheit. Nichts motiviert und ermutigt mich mehr, als zu sehen, wie bei einer Aufführung, einer Show oder einem Workshop Beziehungen entstehen und wachsen. Es ist unglaublich zu sehen, wie schnell aus Fremden Freunde werden, wenn sie die Chance haben, gemeinsam etwas aufzubauen.

Seitu Jones

Multidisziplinärer Künstler, Anwalt und Macher

Der große Künstler und Aktivist Harry Belafonte beschrieb sich selbst nicht als Künstler, der zum Aktivisten wurde, sondern als Aktivist, der zum Künstler wurde und begann, mit Liedern den Weg nach vorn zu weisen. Harry Belafonte sagte: „Künstler sind die Hüter der Wahrheit.“ Unsere Mission ist es, Geschichte zu schreiben. Künstler sind die Träger der Geschichte. Künstler schufen die Malereien an Höhlenwänden und schrieben die Worte des Korans, der Bibel und der Thora hinein. Wir waren diejenigen, die die Lieder schufen, die uns allen halfen, uns zu erheben. Ich hatte immer das Gefühl, dass Künstler helfen können, eine neue Welt zu gestalten.“

Fünf Jahre sind seit dem Mord an George Floyd und der darauffolgenden „rassistischen Abrechnung“ vergangen. Es war ein „Weckruf“ für die Nation und die Welt, der uns alle aufhorchen ließ. Doch für viele von uns war es nicht das erste Mal…

Ich erinnere mich noch gut daran, wie ich mit meinem Vater vor dem Fernseher stand und Walter Cronkite zuhörte, wie er uns vom Tod von Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. erzählte. Am nächsten Tag verließ unsere kleine Gruppe schwarzer Schüler der Washburn High School im Süden von Minneapolis die Schule, um zu einem Gebetsgottesdienst in die örtliche Kirche zu gehen.

Nach langen Debatten zwischen meiner Mutter und meinem Vater darüber, ob wir unsere jährliche Frühlingsreise zu unseren Verwandten in Chicago unternehmen sollten, brachen wir noch am selben Abend zu unserer Osterreise auf, um die Familie meiner Mutter in Chicago zu besuchen. Dort wurden wir Zeugen von Trauer- und Wutausbrüchen, die zu einem der größten öffentlichen Aufstände in den USA nach Dr. Kings Tod führten. Manche Leute bezeichnen diese Unruhen heute als den Aufstand in der Karwoche. Wieder einmal bin ich zu einem Schüler Dr. Kings geworden und habe erkannt, wie sehr seine Philosophien meine eigene künstlerische Arbeit prägen.

Dr. King verbreitete eine revolutionäre Liebe. Cornell West nennt ihn den „Radikalen König“. Allzu oft wird in den heutigen Porträts von Dr. King nicht berücksichtigt, wie sehr er den Status quo störte oder wie bedrohlich sein Konzept, die Bürgerrechtsbewegung, die Antikriegsbewegung, die Frauenbewegung und die Umweltbewegung zu vereinen, für die Machthaber war.

Der große Künstler und Aktivist Harry Belafonte beschrieb sich selbst nicht als Künstler, der zum Aktivisten wurde, sondern als Aktivist, der zum Künstler wurde und begann, mit Liedern den Weg nach vorn zu weisen. Harry Belafonte sagte: „Künstler sind die Hüter der Wahrheit.“ Unsere Mission ist es, Geschichte zu schreiben. Künstler sind die Träger der Geschichte. Künstler schufen die Malereien an Höhlenwänden und die Worte des Korans, der Bibel und der Thora. Wir waren diejenigen, die die Lieder schufen, die uns allen halfen, uns zu erheben. Ich war schon immer der Meinung, dass Künstler helfen können, eine neue Welt zu gestalten.

Dies ist die Grundlage meiner Arbeit als Künstlerin. Arleta Little, die Dichterin und Leiterin des Lofts, schrieb während ihrer Tätigkeit als Programmbeauftragte der McKnight Foundation: „Künstler und Kunstorganisationen kämpfen nicht, weil wir unfähig sind. Wir kämpfen, weil uns Ressourcen und Möglichkeiten strukturell und systematisch vorenthalten werden.“ Es ist nicht unsere Schuld, dass unsere Stimmen nicht lauter sind.

Einige Tage nach der Ermordung George Floyds dachte ich: „Was kann ich tun, um meine Liebe zur Menschheit und meinen Schmerz über den Verlust eines weiteren Schwarzen zum Ausdruck zu bringen?“ Meine Antwort war, Kunst zu schaffen und ein Porträt von George Floyd zu gestalten, das der Welt zur Verfügung steht, um seiner zu gedenken und uns allen den Weg zur Gerechtigkeit zu weisen.

Vor fünf Jahren wurde dieser Weckruf erhört, und eingegangene Verpflichtungen werden nun gebrochen. Wenn wir als Künstler nicht Widerstand leisten und weiterhin gegen Ungerechtigkeit kämpfen, wird dieser Weckruf unerhört bleiben.

David Mura

Memoirenschreiber, Essayist, Romanautor, Dichter, Kritiker, Dramatiker und Performancekünstler

Künstler erzählen, zeigen und erzählen der Macht die Wahrheit; unsere Aufgabe ist es, hinter den Vorhang aus Klischees, Lügen und Gaslighting zu blicken, den die Macht zur Festigung ihrer Macht erschafft. Wie ich meinen Schreibstudenten erzähle, holen wir Schriftsteller Dinge aus dem Schrank oder unter dem Tisch hervor und bringen unangenehme Wahrheiten ans Licht, die die Mächtigen leugnen wollen – ob in einer Familie, einer Gemeinschaft oder einer Nation. Wir Künstler verkomplizieren die uns präsentierten Realitätsbilder. Und wir suchen nicht immer nur nach dem Offensichtlichen, sondern nach einer Sprache, einer Kunst, um auszudrücken, was wir unbewusst wissen, aber noch nicht die Sprache, die Kunst haben, es auszudrücken.

Die Realität, wie auch immer man sie interpretiert, liegt jenseits einer Klischee-Scheibe. Jede Kultur produziert eine solche Scheibe, teils um ihre eigenen Praktiken zu erleichtern (Gewohnheiten zu etablieren), teils um ihre eigene Macht zu festigen. Die Realität ist den Mächtigen feindlich gesinnt. —John Berger, Und unsere Herzen, unsere Gesichter, kurz wie Fotos

Künstler erzählen, zeigen und erzählen der Macht die Wahrheit; unsere Aufgabe ist es, hinter den Vorhang aus Klischees, Lügen und Gaslighting zu blicken, den die Macht zur Festigung ihrer Macht erschafft. Wie ich meinen Schreibstudenten erzähle, holen wir Schriftsteller Dinge aus dem Schrank oder unter dem Tisch hervor und bringen unangenehme Wahrheiten ans Licht, die die Mächtigen leugnen wollen – sei es in einer Familie, einer Gemeinschaft oder einer Nation. Wir Künstler verkomplizieren die uns präsentierten Realitätsbilder. Und wir suchen nicht immer nur nach dem Offensichtlichen, sondern nach einer Sprache, einer Kunst, um auszudrücken, was wir unbewusst wissen, aber noch nicht die Sprache, die Kunst haben, es auszudrücken.

Vielen von uns wird gesagt, dass unsere Geschichten und unsere Stimmen keine Rolle spielen. Doch wenn wir sehen, wie andere aus unserer Gemeinschaft ihre Wahrheiten ausdrücken, aus ihrem Leben erzählen und ihren Sichtweisen, Gedanken und Gefühlen Ausdruck verleihen, fühlen wir uns bestärkt, dasselbe zu tun. Kunst gibt uns diese Freiheit, und Künstler ermutigen andere, diese Freiheit zu nutzen.

Das ist natürlich leichter gesagt als getan. Wir leben offensichtlich in schwierigen Zeiten. In meinem letzten Buch „The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself: Racial Myths and Our American Narratives“ untersuche ich die Lügen, Mythen, Verzerrungen und Auslassungen in vielen Erzählungen weißer Amerikaner über unsere Geschichte und Gegenwart und stelle ihnen die historischen und fiktiven Erzählungen Afroamerikaner über ihr Leben und ihre Erfahrungen gegenüber.

Einer der Kernpunkte des Buches ist, dass es nach jedem scheinbaren Fortschritt in Richtung Rassengleichheit, oft in Form von Gesetzen wie dem 13., 14. und 15. Zusatzartikel zur Verfassung, stets eine rassistische Gegenreaktion gab, bei der sich ein erheblicher, wenn nicht sogar mehrheitlicher Teil der Weißen gegen diese Fortschritte wehrte und versuchte, sie zu untergraben. Ihr Ziel war es, das Land in den vorherigen Zustand der Rassenungleichheit zurückzuführen. Im Rahmen dieser Gegenreaktion versuchten sie, jeden rechtlichen oder politischen Fortschritt in Richtung Gleichberechtigung zu umgehen und zunichtezumachen.

Wir befinden uns mitten in einer solchen Gegenreaktion. Und deshalb dürfen wir nicht vergessen, dass andere vor uns gegen diese Kürzungen und Rückschläge gekämpft haben. Auch sie mussten weiterkämpfen, selbst als ihre Hoffnungen und ihre Freude über vermeintliche Fortschritte zunichte gemacht wurden. Ihr Durchhaltevermögen, ihre Beharrlichkeit haben den Fortschritt und die Rechte, die wir heute wahrnehmen, erst möglich gemacht. Deshalb dürfen wir nicht vergessen, dass wir für die Zukunft kämpfen, so wie die Vergangenheit für uns gekämpft hat – für die Chancen, die uns heute offen stehen und die es früher nicht gab.

Kürzlich sah ich das History-Theater-Stück „Secret Warriors“ von Rick Shiomi. Es erzählt die Geschichte der japanischstämmigen Amerikaner des Militärgeheimdienstes, die in Fort Snelling Japanisch lernten. Diese Soldaten dienten im Zweiten Weltkrieg als Führer auf dem Schlachtfeld, verhörten Gefangene und übersetzten erbeutete oder abgefangene japanische Nachrichten und Dokumente. MacArthurs Geheimdienstchef, General Willoughby, sagte, diese Nisei-Soldaten des Militärgeheimdienstes hätten den Krieg im Pazifik um zwei Jahre verkürzt und eine Million Amerikaner gerettet. Das bedeutet, dass es heute noch antiasiatische und einwanderungsfeindliche Amerikaner gibt, weil diese Nisei-Soldaten dazu beitrugen, ihre Väter und Großväter zu retten.

Und doch wurden viele dieser Nisei und ihre Familien, darunter auch meine Onkel, die im Militärdienst dienten, von der Regierung in Lagern eingesperrt, umgeben von Stacheldrahtzäunen und bewachten Schützentürmen. Ihnen wurde weder ein Gerichtsverfahren noch eine Habeas-Corpus-Anordnung gewährt. Sie kämpften gegen weitaus größere rassistische Vorurteile, als ich sie je erlebt habe. Deshalb bin ich es ihnen und ihrem Andenken schuldig, weiterhin für die Rechte aller Amerikaner zu kämpfen.

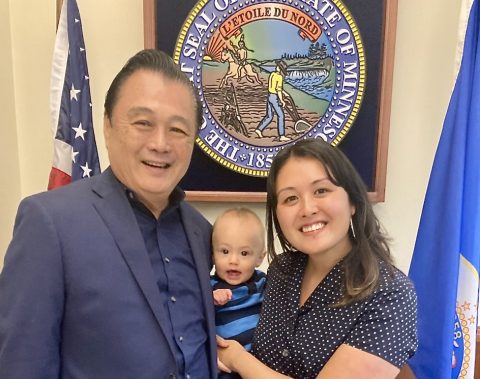

Aber nicht nur die Vergangenheit inspiriert. 2022 wurde meine Tochter die erste japanisch-amerikanische Abgeordnete in Minnesota, als sie für ihren Wahlkreis South Minneapolis ins Repräsentantenhaus gewählt wurde. Sie unterstützte einen Gesetzentwurf für ethnische Studien mit den Worten: „Mein Vater konnte in der Schule nichts über die Internierungslager lernen, und ich konnte in der Schule nichts über die Lager lernen. Ich möchte, dass mein Sohn Tadashi in der Schule etwas über sein japanisch-amerikanisches Erbe lernen kann.“

Trotz der aktuellen Versuche, jede ernsthafte Diskussion über die rassistische Vergangenheit unseres Landes zu unterdrücken, ist dieses Gesetz zu ethnischen Studien in Minnesota immer noch in Kraft. Es ist das Ergebnis des Kampfes der japanisch-amerikanischen Gemeinschaft über vier Generationen. Daher bin ich es meinen Großeltern, meinen Eltern, meinen Kindern und meinem Enkelkind sowie allen, die in unseren Gemeinden gegen Ungerechtigkeit kämpfen, schuldig, diesen Kampf fortzusetzen.

Tish Jones

Dichter, Kulturproduzent und Pädagoge

Gesehen und gehört zu werden, bedeutet einen Heilungsprozess einzuleiten. Daher war und ist unsere Arbeit als Kreative seit jeher in einer heilenden und verändernden Praxis verwurzelt. Kunst, Künstler und Kulturschaffende verwandeln die Gefühle, Energien, Hoffnungen, Überzeugungen und Erfahrungen der Menschen in zeitlose und verständliche Werke, die Momente, Epochen, Überzeugungen und Wahrheiten repräsentieren.

Wie können Kunst/Künstler/Kulturträger zum sozialen Wandel und zur Heilung der Gemeinschaft beitragen?

Gesehen und gehört zu werden, bedeutet einen Heilungsprozess einzuleiten. Daher war und ist unsere Arbeit als Kreative stets in einer heilenden und verändernden Praxis verwurzelt. Kunst, Künstler und Kulturschaffende verwandeln die Gefühle, Energien, Hoffnungen, Überzeugungen und Erfahrungen der Menschen in zeitlose und verständliche Werke, die Momente, Epochen, Überzeugungen und Wahrheiten repräsentieren. Wir schaffen Artefakte und dokumentieren Geschichte. Wir bewahren Kultur. Wir liefern Gegennarrative und formen Realitäten. All dies dient als Katalysator für positive soziale Wirkung, und genau das ist unsere Arbeit.

Was inspiriert oder motiviert Sie in diesen herausfordernden Zeiten?

Schwarze Menschen und Babys. Die Widerstandsfähigkeit, die diese beiden Volksgruppen in ihrer bloßen Existenz und ihrem Überleben/Wachstum zeigen, während sie einer Welt gegenüberstehen, die in keiner Weise auf ihre Sicherheit, ihr Überleben oder ihre Fähigkeit/ihr Potenzial zum Gedeihen ausgerichtet ist, ist zweifellos bemerkenswert.

Shanai Matteson

Schriftsteller, bildender Künstler, Kulturveranstalter

Was ich an Künstlern und Kulturschaffenden besonders liebe, ist die Art und Weise, wie wir uns durch die Kunsträume und Projekte, die wir ermöglichen, ganz neue Welten vorstellen und erschaffen. Ich denke immer wieder darüber nach, wie die Beziehungen entstehen, wenn wir andere einladen, sich gemeinsam mit uns eine andere Welt vorzustellen, einen Raum zu schaffen, in dem diese andere Welt glaubwürdig ist, oder gemeinsam unsere Geschichten erzählen … Wie uns das ermutigen kann, unsere kreative und kollektive Kraft sowie die lebendigen Verbindungen zu unseren Orten und zueinander zu erkennen. Wir werden zu Verfechtern der Gerechtigkeit, weil wir beginnen zu erkennen, wie unsere Geschichten zusammenhängen, und wir werden Teil von etwas Größerem als uns selbst.“

Wie können Kunst/Künstler/Kulturträger zum sozialen Wandel und zur Heilung der Gemeinschaft beitragen?

Was ich an Künstlern und Kulturschaffenden liebe, ist die Art und Weise, wie wir uns durch die Kunsträume und Projekte, die wir ermöglichen, ganz neue Welten vorstellen und erschaffen. Ich denke immer wieder darüber nach, wie die Beziehungen entstehen, wenn wir andere einladen, sich gemeinsam mit uns eine andere Welt vorzustellen, einen Raum zu schaffen, in dem diese andere Welt glaubwürdig ist, oder gemeinsam unsere Geschichten zu erzählen … Wie uns das ermutigen kann, unsere kreative und kollektive Kraft sowie die lebendigen Verbindungen zu unseren Orten und zueinander zu erkennen. Wir werden zu Verfechtern der Gerechtigkeit, weil wir beginnen zu erkennen, wie unsere Geschichten zusammenhängen, und wir werden Teil von etwas Größerem als uns selbst.

Das ist wohl eine umständliche Art zu sagen, dass Künstler oft Querdenker sind und wir Empathie fördern. Als Kulturorganisatorin bringe ich diese Neigung, kreativ zu denken – und Neues auszuprobieren – in die bereits laufenden Bemühungen ein, die Verbindungen, Beziehungen und Fürsorge der Gemeinschaft wiederzubeleben.

Für mich ist das in diesen Zeiten oberste Priorität. Welche Werkzeuge, Fähigkeiten oder welchen Mut haben wir als Künstler oder durch unsere Kultur und Geschichten entwickelt, die wir mit unseren Gemeinschaften teilen können? Wie ermutigen wir andere, indem wir einfach unermüdlich sind, wer wir sind?

Für mich bedeutet das, Räume für das Zusammensein zu schaffen und Anerkennung und Zusammenarbeit zu fördern. Potlucks. Malpartys. Pop-up-Touren. Dazu gehört auch die Entwicklung von Storytelling-Projekten, wie zuletzt Zeitungspublikationen, in denen wir unsere Geschichten erzählen können. Und das hilft, andere Künstler, Kulturschaffende und -organisatoren zu ermutigen, ihre Macht zu nutzen oder die notwendigen Unterstützungsstrukturen an ihren Orten und in ihren Gemeinden zu schaffen.

In einer ländlichen Gemeinde mit niedrigem Einkommen stehen wir vor Herausforderungen, die nicht einzigartig sind, sondern viel mit unseren einzigartigen Orten und Kulturen zu tun haben. Viele von uns sind darauf konditioniert, uns selbst und unsere Nachbarn als klein, isoliert, gespalten und machtlos zu betrachten. Oder als ob andere an anderen Orten uns nicht verstehen, nichts mit uns teilen oder sich nicht für uns einsetzen würden. Doch wir haben viel mit Gemeinden in der Nähe und in der Ferne gemeinsam – und wir sind weder allein noch machtlos. Wir können uns selbst und unsere Nachbarn vertreten.

Ein Großteil meiner Arbeit besteht darin, andere zu ermutigen, sich selbst als kreative Mitwirkende an Kultur und Gemeinschaft zu sehen – als Autoren ihrer eigenen Geschichte – und der kollektiven Geschichte, in der wir gerade leben, einer gefährlichen und schwierigen Zeit, aber auch einer Zeit der Möglichkeiten und revolutionären Ideen.

Ideen.

Ich schaffe künstlerische Räume und Projekte mit anderen in meiner Gemeinschaft, damit ich zeigen kann, wie das aussieht und sich anfühlt, und um andere zu ermutigen, mutig zu sein, ihre Wahrheit zu teilen, die Fürsorge und Kultur der Orte, die wir teilen, zu ehren, solche Dinge.

Es ist mir wichtig zu wissen, dass ich diese Arbeit nie allein mache, sondern eng mit anderen Künstlern und Mitgliedern meiner Community zusammenarbeite. Die Führungspersönlichkeiten, die mich ermutigt haben, inspirieren mich, und ich glaube fest an die Kraft des Volkes. Ich glaube an die Brillanz unserer kreativen Vision, wenn wir uns daran erinnern, wer wir sind und wozu wir gemeinsam fähig sind.

Was inspiriert oder motiviert Sie in diesen herausfordernden Zeiten?

Ich wache jeden Tag auf und bin inspiriert von den Menschen in meiner Gemeinde. Es sind herausfordernde Zeiten, wirklich brutale und herzzerreißende Zeiten, aber ich sehe auf viele stille Weisen, wie Menschen sich den Herausforderungen stellen, füreinander sorgen und sich auf eine ungewisse Zukunft vorbereiten.

Ich lasse mich auch von meinen kreativen Mitarbeitern inspirieren – den Leuten, die nicht nur „Ja“ sagen, wenn wir eine verrückte Idee haben, sondern auch diejenigen, die sagen: „Na, da mache ich mit!“

Annie Humphrey mit Feuer im Dorf, malen wunderschöne Wandgemälde für die Powwow-Gelände des Ball Clubs (erfahren Sie mehr über die Arbeit von Fire in the Village in diese aktuelle Geschichte von KAXE); Meine Mitverschwörer mit Talon Mine Touren, die Führungen durch eine Sulfidmine anbieten, die es nicht gibt, um Geschichten darüber zu erzählen, warum dieser Ort schützenswert ist; und meine lokale Gemeinde mit dem Good Trouble Club.

All diese Kunstprojekte sind echte Gemeinschaftsprojekte. Gemeinsam mit vielen anderen Künstlern und Organisatoren aus Kleinstädten bauen wir meiner Meinung nach eine Bewegung von Landbewohnern auf, die für Gerechtigkeit kämpfen. Es sind natürlich nicht nur Kunstprojekte, sondern auch Bildungsprojekte. Sie dienen der Bildung von Netzwerken gegenseitiger Hilfe und von Selbstverteidigungsvereinen und tragen dazu bei, die öffentliche Meinung und Kultur vor Ort zu verändern.