Category:Impact Story18 min read

Category:Impact Story18 min read

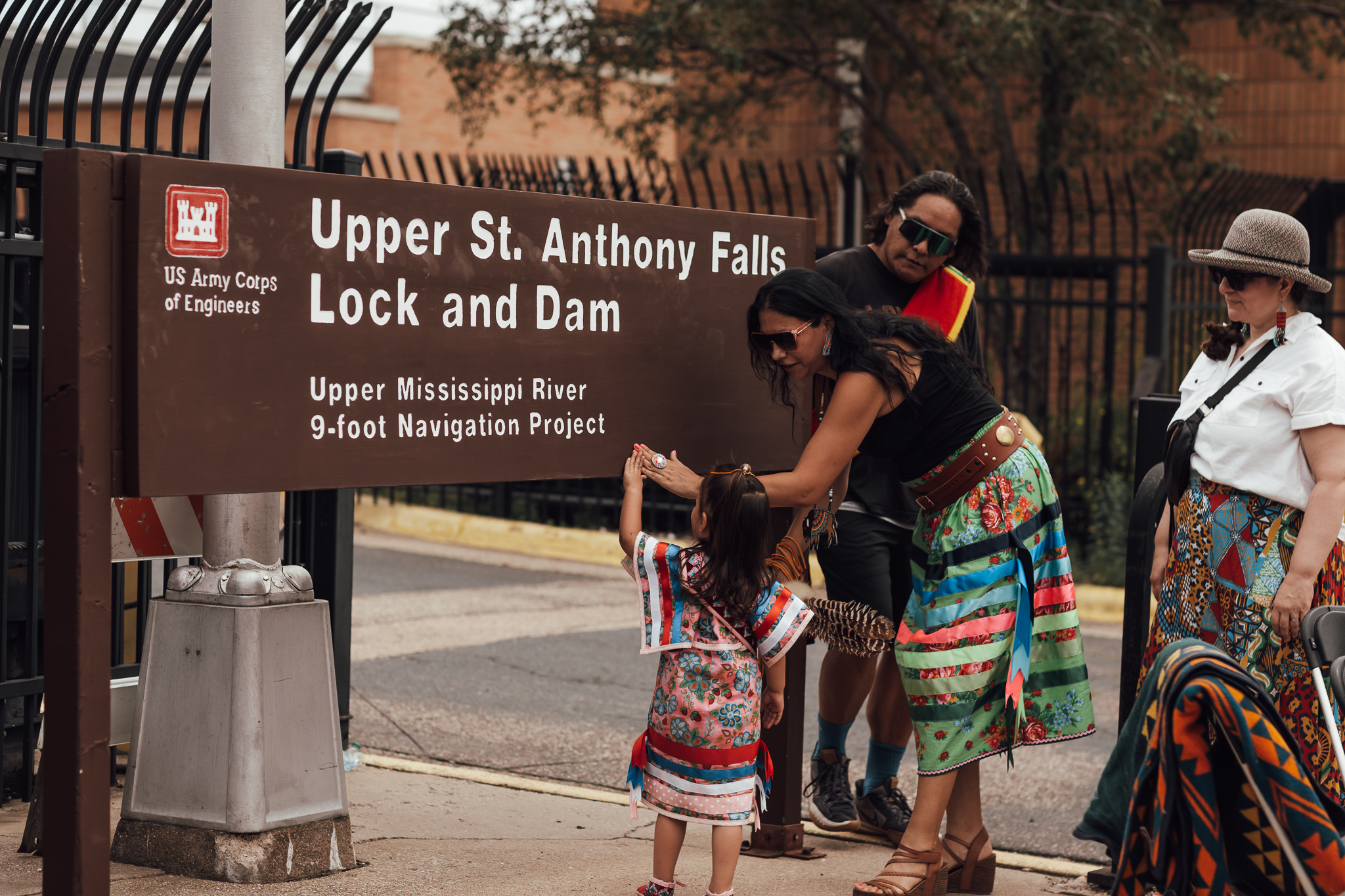

Throughout the different seasons, Minnesotans walk near the Mississippi River, bike, exercise, bring our dogs, and family to see the beauty of the water and to be outdoors. Neighbors and visitors come to the iconic and powerful Owámniyomni, also known as “St. Anthony Falls”.

Fewer people are aware of the erasure of the sacred history of the land, water, and this place to Dakota people, who recognize the area as Dakota homeland in Mni Sóta Makoce (Minnesota). “Owámniyomni” means ‘turbulent waters,’ referring to the bottom of the falls where the water churns, explains Shelley Buck (Prairie Island Indian Community), who serves as the president of Owámniyomni Okhódayapi, a Dakota-led nonprofit organization that is working to restore and transform five acres of land and water on the Minneapolis central riverfront.

“For us, the entire area—not just the falls—is a sacred site,” Buck shares. It is considered a place of gathering, ceremony, and connection to Ȟaȟa Wakpá (Mississippi River) as part of the Dakota cosmology and creation story. “This site is sacred because water is life for us. It was a place where we prayed, and there was a sacred island called Wíta Wanáǧi, or Spirit Island, where women would give birth. It connected the spirit world and the living world. It was a powerful, sacred place full of life,” Buck explains.

By reviving Dakota lifeways of planting and land stewardship, and rebuilding human connection to water for all, Owámniyomni Okhódayapi aims to create a future where Dakota culture and values are embraced in Minnesota’s identity.

“This project is important because it helps educate people about the knowledge we’ve lost—not just Dakota people, but everyone. If you live on Dakota land, you should learn Dakota history,” says Valentina Mgeni (Mdewakanton, Tinta Winta/Prairie Island Indian Community), Tribal council secretary for the Prairie Island Indian Community.

As a result of settler westward expansion, colonization, federal American Indian removal acts, broken treaties, and the Dakota US War of 1862, the Mississippi River was used as a resource, exploited by the lumber and flour industries that boomed in Minnesota at the turn of the century. The Falls, Owámniyomni, were once over 1,250 feet wide, and now are about a third of that size. Spirit Island (Wíta Wanáǧi) was quarried for limestone, and its remains were removed by 1963. Today, the site is largely covered in concrete, a defunct dam and closed visitor center blocking access to much of the water.

“Preserving this site is important because Dakota history has been erased here. All you hear about is the Mill City, but there is a history before colonization and industrialization. We must ensure that history is not forgotten and that Dakota people are not forgotten in their homelands. The entire state of Minnesota is our homeland. We have no migration story; this is where we were born and created. We want our stories told again, for our people to have a voice, and to feel safe and welcomed in our homelands,” Buck says.

For Native people, the removal of Spirit Island and the reshaping of the river was an act of desecration of a sacred site. Through displacement, forced removal, family separation, and genocide, Dakota and Indigenous people were separated from their connection and access to the river, land, and their ways of being.

“This project is important because it brings Dakota people back to their homelands and helps heal from past trauma—boarding schools, children taken from unmarried women, addiction in our communities,” explains Mgeni.

Video by Line Break Media.

As an organization, Owámniyomni Okhódayapi has gone through a few evolutions. Originally, it was called St. Anthony Falls Lock & Dam Conservancy, then Friends of the Lock & Dam, founded by Paul Reyelts and Mark Wilson in 2016 in response to the closure of the Upper Lock to commercial navigation and to prevent further industrialization. The organization transitioned to the name Friends of the Falls in 2020, evolving its mission to protect and honor the falls as the only major waterfall located on the Mississippi River, and refocused by centering Indigenous voices. Congressional legislation was passed in 2020 requiring the Army Corps of Engineers to transfer the site ownership to the City of Minneapolis or its designee. Through this legislation, Owámniyomni Okhódayapi plans to gain ownership of the federal land in 2026.

The Friends were committed to creating an authentic engagement process by centering Native voices and perspectives, and brought Native and non-Native communities together for a shared vision. In 2023, the organization transitioned to Dakota leadership, appointing Shelley Buck as president, and then transformed the name to Owámniyomni Okhódayapi, uplifting the Dakota language and raising visibility and connection to the Dakota homeland. The four Minnesota Dakota Nations found that Owámniyomni Okhódayapi should own the project site for the time being, with the Tribes maintaining control through governance. Long-term, it is Owámniyomni Okhódayapi’s goal for the four Dakota Nations (Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community, Prairie Island Indian Community, Lower Sioux Indian Community, and Upper Sioux Community) to share collective ownership. The organization is committed to absorbing the financial and legal risk associated with restoring this stolen land. To that end, Owámniyomni Okhódayapi has established an endowment to ensure that when the Dakota Tribal Nations assume ownership, they will not inherit a financial burden for land taken from them.

“Dakota-led doesn’t mean Dakota-only—it means Dakota are in the driver’s seat. We’ve had a hundred years of paternalism, which never worked. When the transition happened, Dakota people welcomed non-Dakota as relatives. When Dakota eat, everybody eats. That’s what Dakota-led means,” says Barry Hand (Oglala Sioux), the program director of Owámniyomni Okhódayapi.

Owámniyomni Okhódayapi leans on guidance from a design team that includes a group of Dakota knowledge keepers, representing multiple Dakota Tribes, as well as GGN as the lead design and landscape architecture firm, and Full Circle Indigenous Planning + Design. This model is fundamentally different from typical design teams because Dakota knowledge keepers are helping to lead the design process, and are valued for their cultural knowledge. Owámniyomni Okhódayapi uses a consensus-based model where Tribal Nations, working groups, knowledge keepers, and programming committees all have a voice in the decision-making processes.

Buck explains that one key function of the organization is to bring the Tribes and project stakeholders together. “This is a huge project with many stakeholders: the federal government, the City of Minneapolis, the Park Board, the DNR, MNDOT, Heritage Boards, Xcel Energy, the local community, and the four Dakota Tribes. Coordination is complex, but everyone has been helpful. We created a Tribal working group appointed by Tribal leaders, who meet regularly with each Tribe, and include Dakota knowledge-keepers at the center of the design process from start to finish. They are paid as contractors because their knowledge is specialized and invaluable. This ensures the project is truly Dakota-led and Dakota-visioned,” Buck says.

Following a decade of intentional relationship building, engagement, and visioning, in November 2025, Owámniyomni Okhódayapi released a design for the cultural and environmental restoration of Owámniyomni. The project will restore five acres of land and water on the central riverfront. The construction is split into two phases, beginning with Land Transformation, preparing the site and plantings starting in spring 2026; and then Water Transformation, focusing on a 25-foot water cascade and shoreline, removing the fencing and concrete structures that have prevented access to the river for decades and returning the original conditions of the site.

Juanita Corbine Espinosa (Spirit Lake Nation, Turtle Mountain & Lac Courte Oreilles Descendant), a Dakota Knowledge Keeper on the design team, says the initiative is about more than construction: “This project isn’t about building monuments; it’s about rebuilding relationships—with the river, the land, the wildlife, and with ourselves. The gentleness of the design calls people to come, to sit, to listen, to experience the power and beauty of Owámniyomni—and to remember that what we do for the river, it does for us.”

The plan includes restoration of Native plant species like oak savanna and upland prairies. Seeds and soil sourced from Dakota Tribal land will be be reintroduced to the site, as well as ecological restoration and natural habitats helping support migratory birds, fish, and wildlife. There will also be ADA-accessible pathways connecting Owámniyomni and the riverfront to the Stone Arch Bridge and Minneapolis trails.

Owámniyomni Okhódayapi has established a unique relationship to the Minneapolis Parks and Recreation Board, ensuring that the Owámniyomni project, Water Works and Mill Ruins Parks are experienced as one place. Michael Schroeder, the assistant superintendent for planning services at the Park Board, leads the design and planning of current and future park systems in Minneapolis. “I posed the idea of a cultural conservation easement. I said I didn’t know what to call it because it’s difficult to conceive of granting to an Indigenous community an easement for land that was taken from them.” The cultural conservation easement enabled Owámniyomni Okhódayapi to use the site in ways that would celebrate Dakota heritage and invite others to learn and benefit from what they are doing on the site, as well as reestablishing a better relationship between the land and water.

“This is a really significant area that has been a highly disturbed landscape that I would hope can one day regain its kind of spiritual importance to Dakota people and others that they once had before Europeans arrived and began changing and harnessing the power of the river,” Schroeder says. When the construction is completed, the restoration of the central riverfront will significantly improve wildlife habitats and human experience at one of Minnesota’s most iconic outdoor spaces.

Use the slider above to see before and after views of the area below the falls based on Owámniyomni Okhódayapi’s plans. Rendering by landscape architecture firm GGN. Click here to see more designs.

For Dakota people, culture and land are interconnected. Owámniyomni Okhódayapi unifies care for place and culture. The organization has been taking care of the physical site through a combination of Indigenous and western land management practices, from harvesting, plant propagation, and cultural burns to mowing, trash collection, and snow removal. Their programming focuses on cultural maintenance by helping sustain the Dakota way of life, including language preservation, ceremonies, and through art, music, and song. Storytelling, such as interpretation, educational initiatives, and the sharing of oral history, is an important method of ensuring Dakota people are visible in their homelands.

To tell the project’s powerful story, Owámniyomni Okhódayapi has published Dakota Lifeway videos connecting all audiences to traditional Dakota practices, stories, and teachings based on the changing seasons around culture, food, language, and more. They also offer self-guided audio tours and monthly interpretive tours.

The project receives funding from multiple sources, including grants from the State of Minnesota, individual donors, and philanthropies like the McKnight Foundation. The majority of state funds are restricted for capital expenses and can’t support work for government relations, engagement, design development, or development of the organization. That means support from foundations is especially important.

“Philanthropy has a unique ability to be flexible,” says Muneer Karcher-Ramos, director of McKnight’s Vibrant & Equitable Communities program. “We can decide how to structure the money and the capital, which can be very different from governmental players. As philanthropy, we can leave it as wide open as we want, and that is what McKnight decided. This allows the community to use funds in ways that make the most sense for them and accelerate the project, instead of putting a lot of red tape around it. We said, let’s get rid of that red tape and invest in ways that make sense for the community.”

“Philanthropy, like support from McKnight Foundation, has been transformative, allowing us to move faster and cover costs for outreach and operations. We want everyone to feel part of this project because it benefits all. When Dakota people thrive, everyone thrives. This is about building a new table where all are welcome,” Buck shares.

“We are trying to reimagine how we relate to Indigenous populations in Minnesota—as we think about sacred sites, Native Nations, and urban populations,” Karcher-Ramos says. “It’s about holding tight to understanding how we can flex in different ways to meet communities where they are and honor what they value. Sometimes organizations hold their strategy so precious that they don’t meet the community where it’s at. As we think about how we want to relate with Minnesota’s Indigenous communities, it’s about truly meeting them where they are.”

Owámniyomni Okhódayapi is making a significant difference for Dakota people, the broader public, and the land by centering Dakota perspectives, enhancing visibility, engagement, and education through the restoration and reconciliation work and collaborations. The organization is gaining momentum in healing our relationships with land and water by also transforming ourselves.

“This land will be restored to prairie. There was a question about building an interpretive center, but our elders and knowledge keepers said, ‘There are enough buildings. We need more of the creation.’ This is the Mississippi Flyway, a vital route for songbirds. When we do culturally informed restoration, we listen to the land because our culture tells us we came from it,” Hand reflects. “Dakota-led means honoring everyone—the fliers, crawlers, four-legged, swimmers, growers, and two-legged. The creator doesn’t differentiate; we’re all two-legged.”

The Owámniyomni Okhódayapi project is creating a model for community-driven, Native-led restoration that can be replicated in other communities in Minnesota and beyond. This wouldn’t be possible without philanthropy’s critical role in resourcing projects like this, by allowing Indigenous leaders to lead instead of being held by bureaucracy, allowing organizations to focus on their mission and amplify their impact of protecting land and water, while uplifting Tribal knowledge and helping our collective future.

“In terms of reconciliation, recognizing that we’re kind of bound by the same idea that we’re stewards of land. That we need to take care of this land, not just for us, but for future generations, is a baseline that we share. And so there’s a common purpose in working with not just Dakota, but other Indigenous peoples to try to help understand how we can use the land effectively for everybody that occupies our community now,” says Schroeder.